Heretic Ending Explained: What Is the One True Religion?

Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

This article contains spoilers for Heretic. If you’re here to find out if there’s a post-credits scene, there is not.

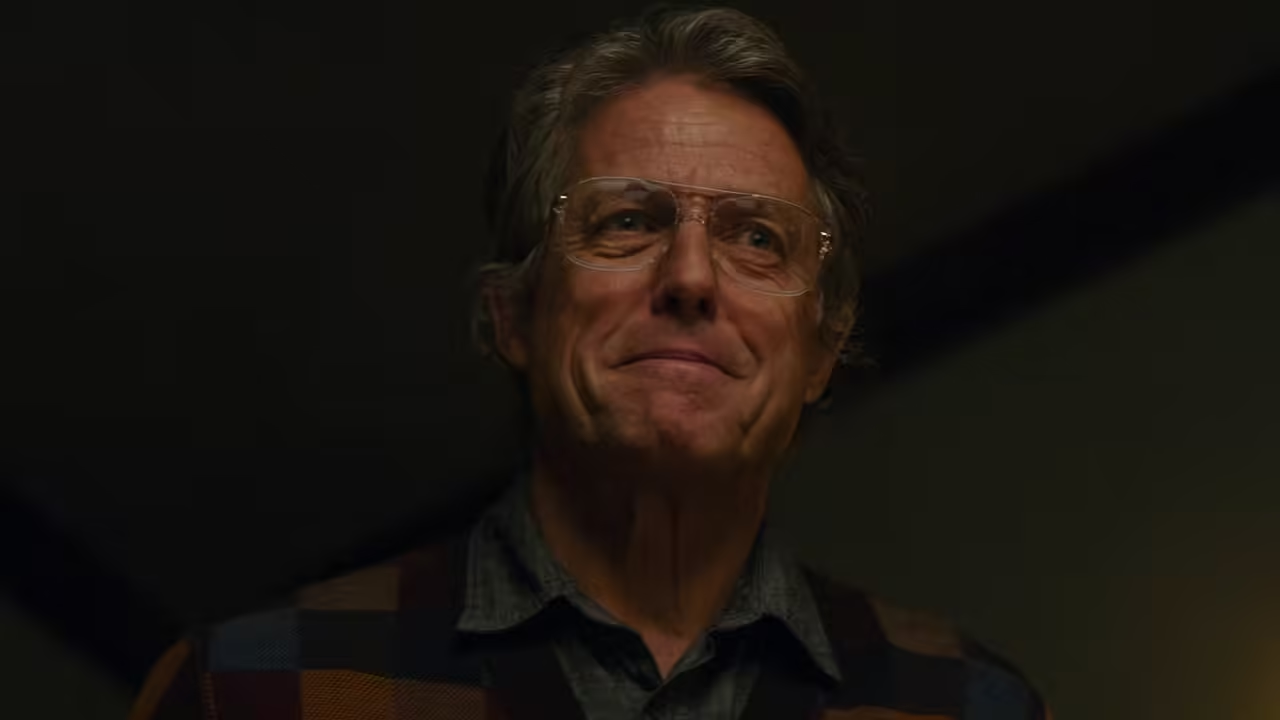

Heretic was always going to be a film that relied on its performances. Going in, we assume that it will be a chamber piece focusing on two Mormon missionaries trying to convert an old man to their religion, which requires some hefty acting from all three of its leads if the audience is to remain engaged. Those performances are all there in spades, but by Act 3 we know that things aren’t what they seem and we’ll be going well beyond a cozy living room chat about religion.

Sister Barnes (Sophie Thatcher) and Sister Paxton (Chloe East) arrive at Mr. Reed’s (Hugh Grant) home right as a blizzard starts to hit. The seemingly kind man invites the freezing missionaries into his living room, insisting that his wife is just in the kitchen baking a blueberry pie. Able to smell the confection, the two girls reluctantly enter the home with the caveat that Mr. Reed’s wife must join them as soon as she’s done baking.

Regrettably, Mrs. Reed is completely made up, Mr. Reed fabricated the smell with a scented candle, and he’s got a whole host of tricks and traps in his unhinged doom house, specifically devised, he insists, to challenge faith in order to find the one true religion.

Heretic Ending Explained

An important thing to know going into Heretic is that there isn’t really a second act. One could kind of argue that one is there for the brief window when Reed traps the girls in the basement and Sister Barnes is still alive, but it mostly just doesn’t exist. One moment the three are having a lively debate about faith, who’s right, and whether or not Mr. Reed should convert, and the next both Sisters are trapped in a murder basement staring down a supposed prophet.

Reed is able to trap the Sisters in the basement by presenting the illusion of choice. Much of the film’s runtime is Grant pulling out every ounce of charisma (which we, after years of his films, know to be quite a lot) as he cheerfully tells the girls that they’re free to leave at any time. But that freedom was never there, and the choices were all illusions.

After the girls end up in the basement, Sister Barnes has had enough. She actively begins to challenge Mr. Reed, while the more timid sister watches on. The final straw is Reed’s prophet trick, in which a bedraggled woman is pulled from yet another unseen corridor in the basement from hell, fed poison, dies, and then miraculously returns to share what God told her.

Sister Barnes can’t pinpoint why at first, but she knows it to be bullshit. But before she can prove it, Mr. Reed slits her throat, insisting to the horrified Sister Paxton that her partner will spring back to life at any moment, bringing with her prophecies and untold wisdom. When that obviously doesn’t happen, Reed gasps in horror as he “realizes” the scar on Sister Barnes’ arm (he had seen it when they were drinking tea in the living room earlier and chooses to use it to his benefit). The apparently mortified man begins to insist that “they’ve chipped her” and rambles on about some conspiracy as the girl bleeds out and takes her final breath, knowing all along that the scar on her arm was for Nexplanon — a birth control implant.

It’s here that the film’s tone takes a hard shift, with Mr. Reed morphing from curious (but obviously nefarious) objector to deranged conspiracy theorist. But, as Sister Paxton navigates deeper into the basement’s labyrinth, she learns that Mr. Reed was neither seeking faith, nor was he mentally ill. He had, in his mind, already found the one true religion.

Sister Paxton eventually realizes that the “prophet” was not one woman, but two (with the first being killed for the singular purpose of challenging the sisters) and stumbles upon a room filled with starved and half-frozen women locked up in cages. The second woman who had uttered the nonsense “prophecy” had included a warning that helped Sister Paxton come to this realization. Mr. Reed lops off a part of her finger with gardening sheers for her trouble, and cheerfully chitchats with Sister Paxton to see if she has come to the realization of what his fabled one true religion might be.

It’s control. Not gods or prophets or spirits, just one dorky creep with cages full of women in his basement, hellbent on exercising his power over the women he’s trapped.

After this revelation, the rest of the film plays out pretty much as you’d expect with one last shock. Sister Paxton fights to escape and manages to make it back to the main basement chamber where Sister Barnes’ body lays. It’s here that her final showdown with Mr. Reed unfolds, with the battle no longer being one of wits but for her life. It seems that Mr. Reed will come out victorious for a moment, dooming Sister Paxton to the same fate as her friend or to a short life in one of the man’s cages. But, just as victory starts to seem impossible, Sister Barnes (who, as you’ll recall, was believed to be dead) springs up with the last vestiges of her strength and helps Sister Paxton kill Mr. Reed. Sister Barnes then dies.

We get the implication that Sister Paxton will go on living — albeit a little less bright-eyed as she’d been at the beginning of Heretic — as she wanders out into the blizzard, but the apparent point of the movie remains rooted in Reed’s thirst for control to the point that it has become his religion.

Do you think The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has psychiatrists on call?

Does Heretic Have a Post-Credits Scene?

As noted earlier, Heretic does not have any post-credits scenes. There is, however, a “No Generative AI was used in the making of this film” note during the credits scroll.