The Boy and the Heron Review

Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

The Boy and the Heron premieres in theaters December 8. This review is based on a screening at the 2023 Toronto International Film Festival.

When Hayao Miyazaki announced his retirement after The Wind Rises in 2013, it made perfect sense. Animation takes a long time, the Studio Ghibil cofounder wasn’t getting any younger, and a biopic about aviation pioneer Jiro Horikoshi acted as a perfect coda to Miyazaki’s career, signaling a maestro going out with a film different in tone and scope than his previous work. The Wind Rises was a deeply personal story about a topic close to the filmmaker that also commented on the perception of and response to his entire body of work.

So when the news broke that Miyazaki was coming out of retirement yet again, it was exciting – but it put even more pressure on the new project. The Boy and the Heron needs to answer two questions: Does it serve as a better ending to a legendary animator’s career than The Wind Rises? And does Miyazaki have anything new to say?

For the former, it depends on what you expect out of a final (until he decides to un-retire again) Miyazaki movie. The Boy and the Heron feels like a return to form of sorts, heavily mirroring Miyazaki’s earlier work in tone and story – it, at times, veers a bit too close to My Neighbor Totoro in terms of subject matter – by telling the tale of a kid escaping into fantasy to avoid facing some hard truths.

Yet Miyazaki isn’t repeating himself, at least not without purpose. When The Boy and the Heron echoes Totoro or Spirited Away in its menagerie of make-believe creatures and adorable little beings, or in fantastical sequence after fantastical sequence, it does so with the added benefit of a director with decades more experience. The film may be surprisingly funny and whimsical at times – in a way, the movie is an isekai, proving that eventually, all anime becomes a fantasy set in another world – but it also looks at this world with a mature eye. A simple moment of a boy trying to get out of school by injuring himself is portrayed extremely graphically to show the weight behind his choices.

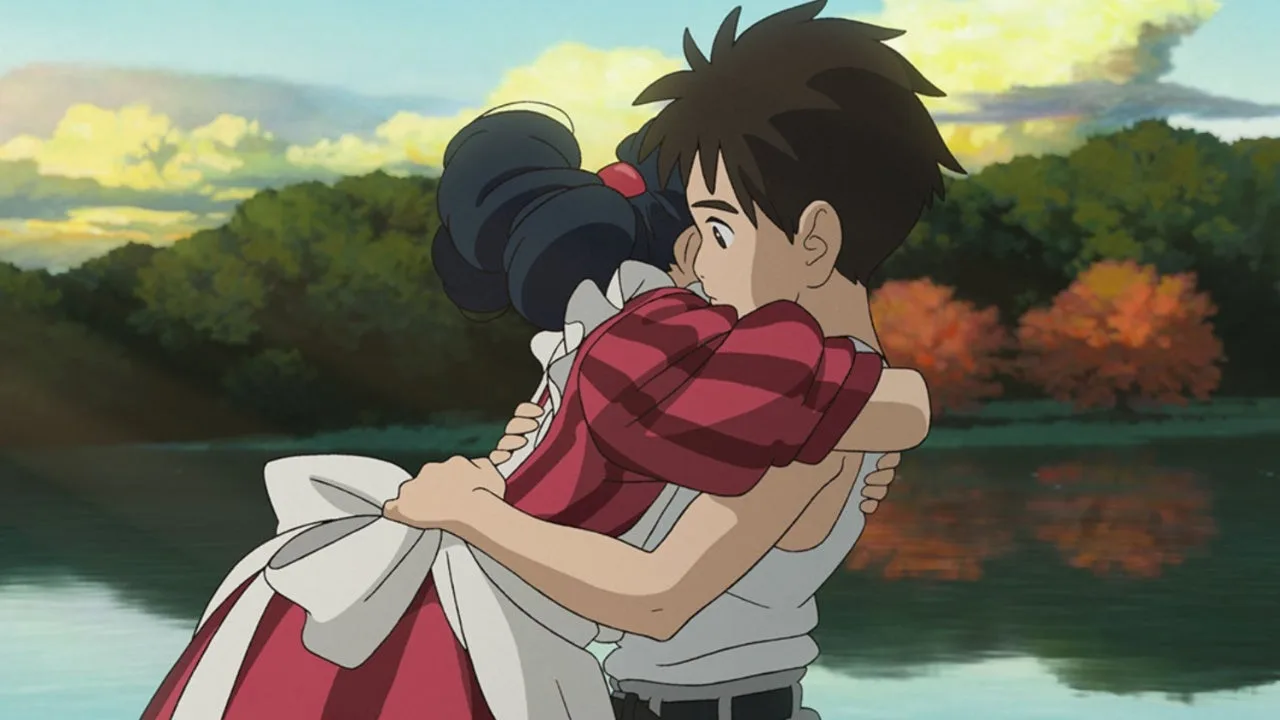

If nothing else, The Boy and the Heron is utterly gorgeous

If nothing else, The Boy and the Heron is utterly gorgeous, Miyazaki’s most visually complex and impressive movie. The set pieces and the worldbuilding are dazzling, particularly in the opening scene of a boy running through the streets of Tokyo during a huge fire, the people in the background fading into shadows in the smoke. While Ghibli movies have always looked beautiful (for the most part), this one feels like a swan song for the animation industry as a whole: An imagery-first experience that goes long stretches of time with no dialogue, in which characters move slowly and quietly, exquisitely employing the concept of “ma” (or empty space) in a way that puts the mainstream American studios and Miyazaki’s Japanese peers to shame. It’s a rare film that’s wholly original and aesthetically pleasing, yet also quite intimate and moving.

As for whether Miyazaki has anything new to say, or do, The Boy and the Heron definitely delivers. This is simultaneously a kids’ movie and a farewell from a man contemplating his own mortality, his legacy, and what awaits those who come after him. Miyazaki reportedly made the film to prepare his grandson for the eventual death of his grandfather, and it shows. Its original (much, much better) Japanese title, How Do You Live?, is intrinsically connected to its story of grief and loss – How Do You Live (On, After Losing a Loved One) would be a more accurate title. This is the most emotionally raw Miyazaki has ever gotten, and longtime Ghibli composer Joe Hisaishi more than meets the challenge with a hauntingly beautiful score that is both playful and devastating – as if the first 10 minutes of Up were the whole movie.

The Boy and the Heron is a perfect encapsulation of who Hayao Miyazaki is, and there’s a lot of him in it – more so than even The Wind Rises. Our protagonist is a kid angry at the world – like Miyazaki himself, as seen in his earlier movies like Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and Princess Mononoke – and there are further parallels to the filmmaker’s relationship with his mother, and his father’s work in a factory manufacturing plane parts during World War II. The war features prominently, especially its smaller impacts on daily life like scarcity of certain foods and luxuries like cigarettes.

In that regard, The Boy and the Heron serves as a final statement, a legendary director looking back at his history of telling hugely entertaining yet profound stories, while also contemplating the world he leaves behind for his grandson. It’s a letter to younger generations, arguing that fantasies are fun, but shouldn’t be dwelled upon. Even if you’re angry at a world that is continuously getting worse, The Boy and the Heron says, you should still face reality – a surprising thematic overlap with the last Evangelion movie, made by a protege of Miyazaki’s.

If this is to be Miyazaki’s final film, it’s his version of the fateful message from My Hero Academia: “Next, it’s your turn.” The Boy and the Heron is a warning and a challenge to anyone who dares try to imitate him, but also a word of encouragement to the next generation to pick up the mantle and be better than their predecessors.