TR-49

“But how can a novel…be fake?” my friend astutely pointed out as I was trying to explain the premise behind inkle’s TR-49. Because the authors never existed? No, there are plenty of instances of pen names and disputed authorship. Because there were no records of these books outside one instance buried deep within an attic? That seems closer to accurate. Add that these titles were likely created by British Intelligence during World War II, and these questions and the books themselves become much more intriguing.

These real-life objects and events set up an incredibly effective frame for the game itself. In fact, most of the promotional material for TR-49 aside from the trailers center around this inspiration, with a detailed letter from the Narrative Director (who was also a mathematician consultant for the Imitation Game film) describing why he believes his relative worked at Bletchley Park specifically, and even an interactive pinboard connecting the novel covers with internal pages. Right away, I became curious how this would fit with inkle’s tendency to play with genre and willingness to experiment with different structures and gameplay mechanics. How do these two things mesh?

One common thread among inkle games is that they encourage you to explore, try different actions and responses and—especially in my experiences with Overboard! and Expelled!—fail in order to learn. They also strive for open-ended, interactive storytelling. Otherwise, their works differ widely in tone, narrative delivery and structure, and gameplay mechanics that intersect with the storytelling. My first impression from trailers and TR-49‘s opening was that it’s intentionally limited in some important ways, like a single setting at the machine and limited direct character interactions, in order to focus the narrative and balance the expansive, association-based puzzle solving.

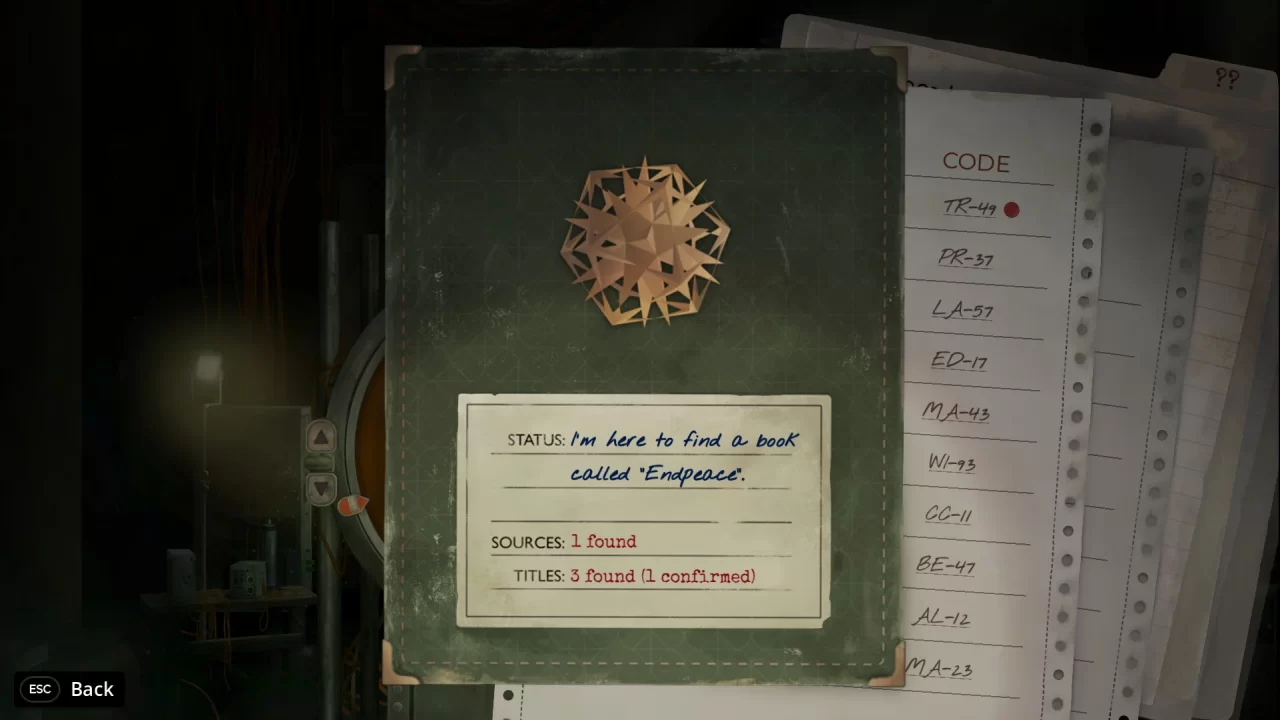

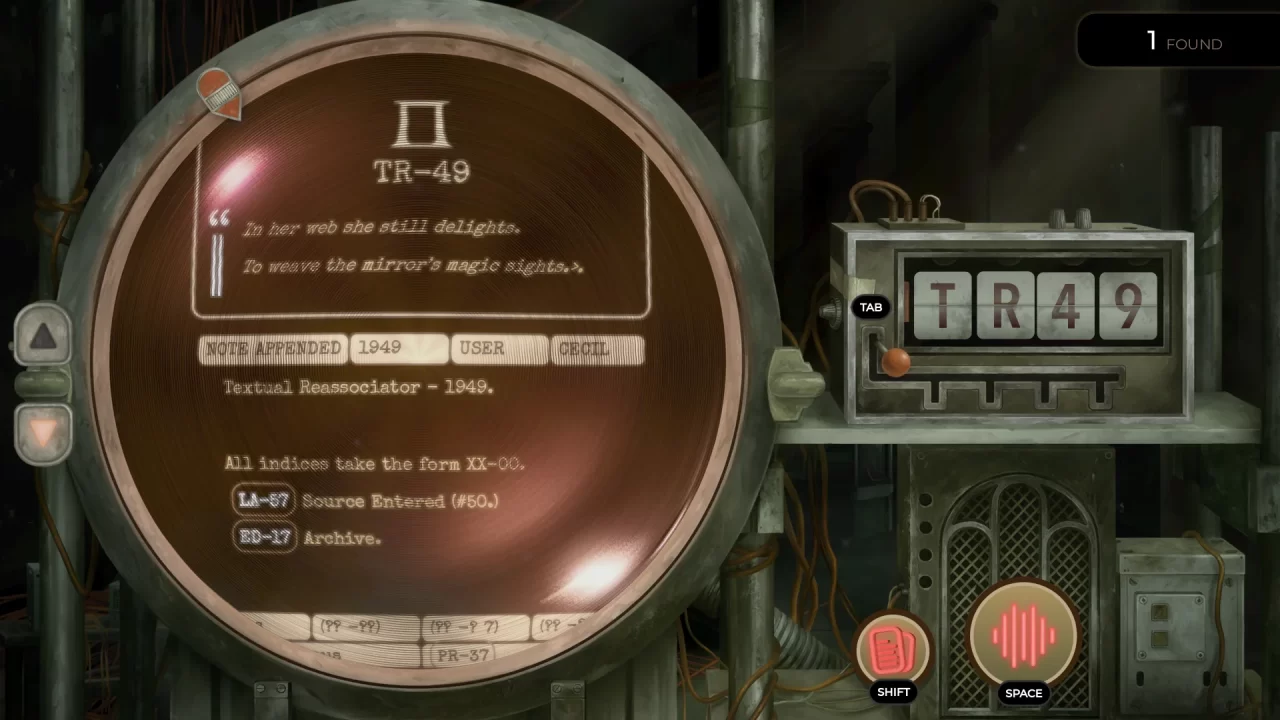

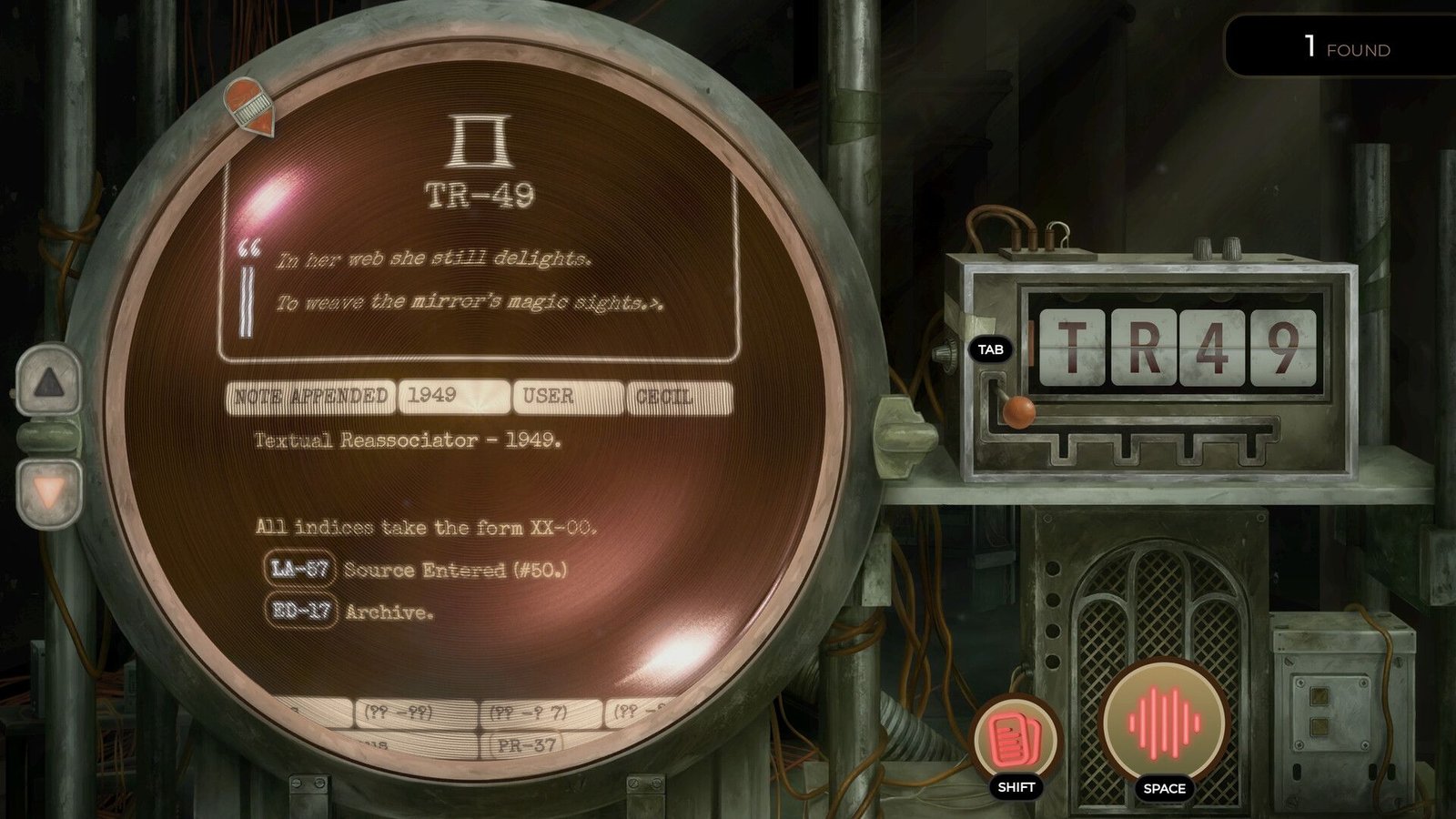

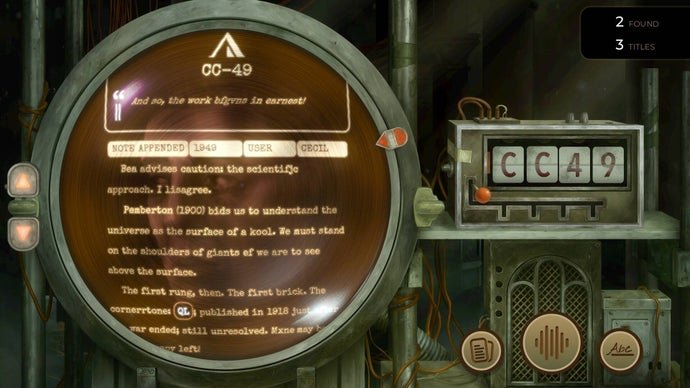

The act of playing TR-49 is another aspect that feels intentionally constrained. There’s a first-person view, seemingly from Abbi’s perspective, looking at the machine’s interface while operating it. The entirety of the game occurs at this interface, with an intercom as your only link to the external world. It’s also a tight loop of examining entries, reading notes, talking to your “handler” Liam every so often, and repeating. This could be very monotonous, but it does not feel that way because the game encourages you to freely imagine associations between entries and figure out codes for new books. A simple example: you read an entry and notice a reference to another work the author wrote “two years later.” You could try adding two to your existing code, as the numbers often reference years or dates. This process feels conducive to a flow state until you hit the next dead end, though I never was stuck for long and was able to quickly find new leads to follow, especially after leaving the game and coming back.

This flexibility in finding codes to identify the machine’s entries and command processes absolutely leads to trial and error, and sometimes even stumbling unintentionally into new information. There was even a time when a typo I made actually connected to an entry. I know some would see this as a flaw—lack of clear direction. I would argue that your direction is always very clear: Explore. Find connections between entries and identify book titles so you can find one specific book that influenced current events. It’s up to the player what that process looks like, and I understand that may not be enough direction for some players to enjoy the game. You’re making associations using every resource at your disposal, and that includes random good luck. I also felt this was good for immersion, because it’s an organic way to solve a problem or puzzle.

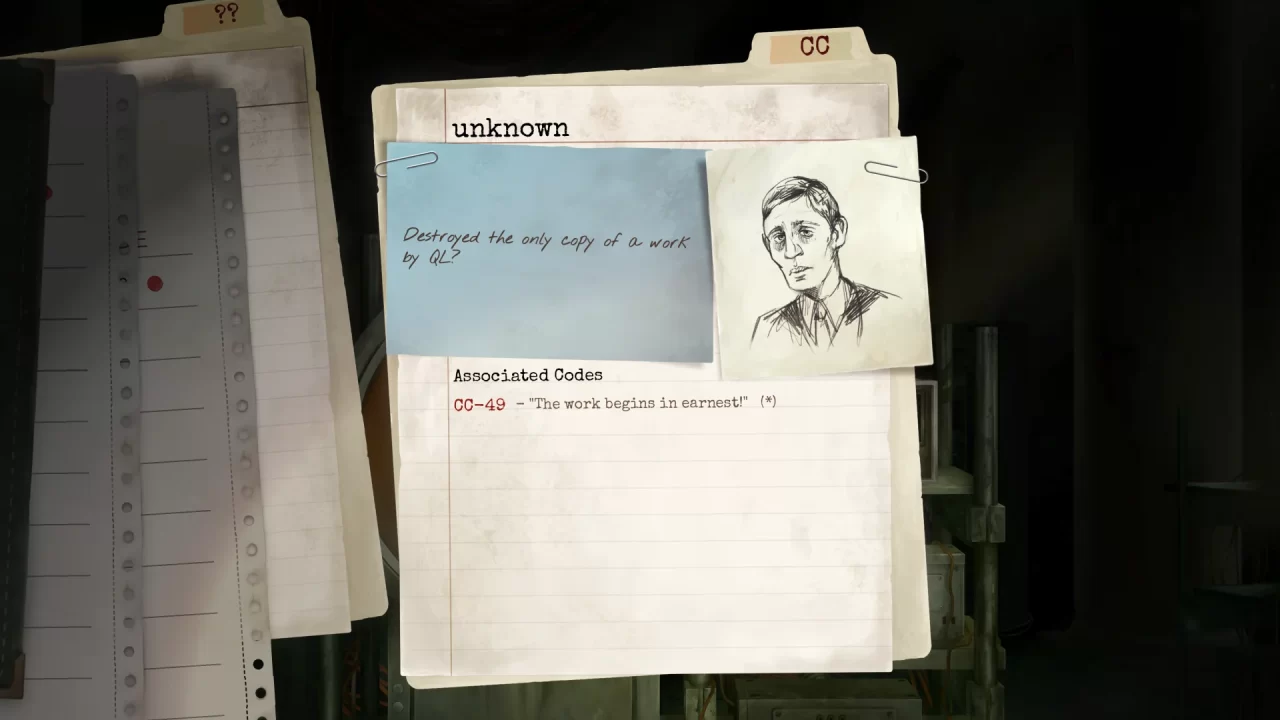

Several unique story threads accomplish the heavy narrative lifting in TR-49. It goes far beyond Abbi and Liam’s story, which has some truly effective tense moments. While they are working to understand how the machine works 50 years after its creation, they uncover the story of the family that created the machine and how it became capable of changing reality. It’s also the story of the authors and texts that were loaded into the machine and reactions to these works from publishers and academic journals. By the time I finished the game, the frame story of the developers uncovering mysterious, direct ties to the setting served as yet another thread to incorporate into the experience. I love how TR-49 incorporates inkle’s love of stories by emphasizing the critical role that feeding literature and important cultural texts has in the code-breaking machine’s amazing reality-bending abilities. (Side note: please forgive me for deleting the Bible entry. I only did it because it is so significant! I had to find the right thing to delete to save the world.)

And this is the perfect point to bring up just how atmospheric TR-49 is. The presentation is fantastic, from sketches of characters and symbols in your notes to the haunting glimpses of portraits you occasionally see in the background of the machine’s display. The muted, lived-in tones of TR-49‘s color palette cries out, “It’s nostalgic, but there’s something off,” while the machine itself instantly evokes photos of code-breaking apparatuses from the time, like the Bombe or Colossus machines used by the British in World War II. Many female cast members, especially the ones directly working with the machine, made TR-49 feel true to the historical role of women in intelligence, and specifically Bletchley Park.

The one mechanic that broke my immersion slightly was the intercom where Abbi and Liam can supposedly interact at any time. It looked like the game was prompting me to use it at times, yet there were also stretches where it was quiet when I tried to use it. I’ll also admit to flailing a bit when I saw the intercom button light up while I was in the middle of typing a code for an entry. The sound design and voice acting were consistently good and not part of this issue at all. Seeing Laurence Chapman (A Highland Song, Heaven’s Vault) return for music was also exciting news, and this time, he delivers a more sparse score with memorable stings at just the right moments, rather similar to Myst or Riven.

On the whole, I felt very invested and excited when I made progress, and that only increased as I reached the end of the story. I realized I had a very specific trajectory and sequence to my game that was most likely unique to me, which very few games accomplish. I wanted to confirm this, so I even had an RPGFan colleague sit down and trial the game so I could observe. Unsurprisingly, his experience was noticeably different from mine as he focused on entries and information that caught his notice. This variety makes for a unique and compelling experience. Still, I would hesitate to recommend TR-49 unilaterally. It demands a specific mood and mindset, but if there’s a match there, it’s like cracking a code and your reward for meeting these demands is thoughtful, flow-like immersion to reveal an engaging story. One that decidedly does not feel fake when you experience it.